"A scientific discovery has no merit unless it can be explained to a barmaid.” This quote by Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford could be applied to the recent achievements of Libor Šmejkal.

He was selected from hundreds of nominated scientists to be awarded the Breakthrough Scientific Discovery of the Year 2023 title in the Falling Walls competition for his theoretical work on altermagnetism and non-dissipative nanoelectronics.

He was able to explain his discoveries to the general public by comparing a new form of magnetism to the dance of swans. His scientific career illustrates the importance of the role of teachers and mentors and symbolises a commitment to discovery and contribution to scientific knowledge.

In the Falling Walls Science Summit, you won the Science Breakthrough of the Year 2023 award against strong competition. Could you tell us about your preparation and the process which led to the honour?

It all started in Dresden after a conference in a bar, where I was explaining our research to a friend, and he decided to nominate me for Falling Walls. I was delighted to be given the opportunity to represent the community that has developed around our research on magnetic quantum matter at Institutes of Physics in Prague and Mainz and now in many places around the world, and I particularly enjoyed the fact that it was a completely different format to the usual conferences. The Berlin Falling Walls Foundation allows scientists to show that they are currently working on something that can be useful for our society.

I gave two talks in Berlin, one to present our work go a general audience, and the other which was more scientific. I had the help of two business presentation experts to explain our complicated magnets to as wide an audience as possible, which was very helpful.

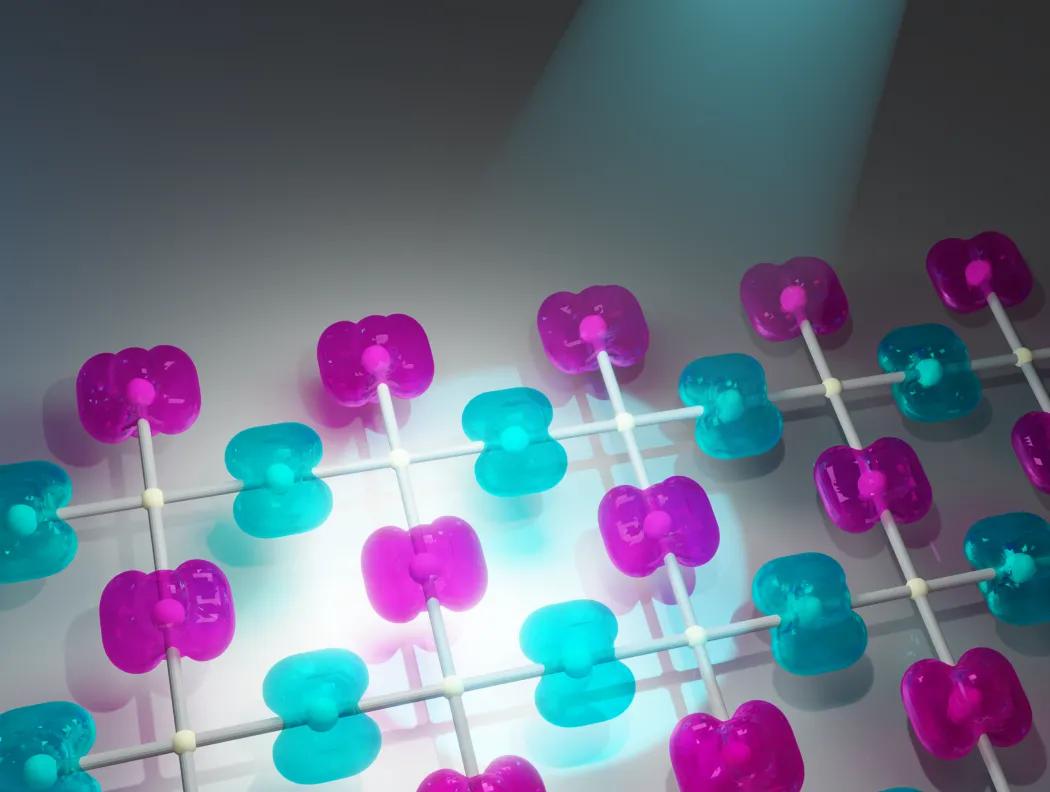

During brainstorming, we came up with the idea that I would start with the invisible forces of magnets, showing that there is something we can't see but can feel, and end with the motion of spins and electrons, which I would explain using a dancing couple. The couple eventually splits, and the dancers go in two different directions into the audience, just as the two types of spin flow in two directions in our magnets.

Judging by the enthusiastic response, the audience really appreciated the professional performance of the dancers. We also hope that it demonstrated how our research into magnets can be useful not only for extending our fundamental knowledge, but also for future low-loss electronics.

Nemáte povoleny cookies, které jsou nutné pro přehrání tohoto obsahu, který je hostován třetí stranou.

Upravit nastavení cookies

(po úpravě nastavení prosím stránku aktualizujte)

In physics, scientists are usually involved in either experiment, application, or theory. You've chosen to combine the directions; you seem to have a taste for the trifecta...

I haves studied at the Masaryk University in Brno where it was possible to do both experiment and theory, although they are two independent fields at the university. I also wanted to find a third direction that was close to technology. For my PhD, I was looking for a topic that would fit this combination as closely as possible, and I was fascinated by the worldwide achievements of Professor Tomas Jungwirth.

When I found out that Tomáš was also working at the Institute of Physics in the Czech Republic, I approached Professor Václav Holý at Charles University and told him that I would like to do my PhD under Tomáš. "Why would Tomáš want you as a PhD student when he doesn't even have a vacancy?" But then he dialled Tomáš's number, for which I thank him very much, he passed me the phone and I started: "This is Libor, I would like to do a doctorate with you." Tomáš was surprised, but then he suggested we meet, and I think we clicked both on a human level and on a scientific level, and that was the beginning of our research together ten years ago.

What is life like for a scientist who works at both the Institute of Physics of the Academy of Sciences and the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz?

Currently, we are performing quantum mechanical calculations with our colleagues and coordinating experiments to verify them. However, for the past few months, I have been primarily focused on writing and defending grants. While I enjoy this work, it is very different from the excitement of discovery. Scientists who have a grant can dedicate more time to writing their next proposal. Tomas and Jairo Sinova in Mainz, who I have learned a lot from, are excellent mentors and coordinate scientific visions very effectively.

Scientific collaborations are also crucial. We participate in grants involving around twenty research groups in Prague and Germany, and globally we have hundreds of collaborations that are constantly increasing. This is also due to Professor Jairo Sinova's initiative, who organizes multiple conferences annually at the University of Mainz, facilitating the formation of new collaborations.

Returning to the daily life of a scientist and recent discoveries, I am fortunate to work in an environment established by Tomas or Jairo, where there are no limits to discovering new scientific solutions. For instance, we have the opportunity to provide a solution to an experiment anywhere in the world if required. There is a strong collaboration with colleagues who provide valuable feedback on experiment feasibility and produce computer-predicted materials atom by atom. The process is dynamic, and I am eager to receive updates on calculations and measurements each day I wake up.

Tomáš, Jairo and I have published a paper in Nature recently after ten years of work. We discovered a new class of magnet, called altermagnets, which exhibit a strong splitting of spins. This property has potential applications in science and technology. The atomic fields in our magnets are thousands of times stronger than those of a fridge magnet. The prediction garnered significant attention due to its unexpected success.

However, through collaboration with Juraj Krempasky and his colleagues from Switzerland, we were able to verify our predictions of split spectra through photoemission at the synchrotron. The measurements made by Juraj aligned precisely with our predictions. When observing that real electrons and wave functions behave as expected, one reaches the limits of human knowledge. This feeling is comparable to the excitement and adrenalin from skiing or scoring a goal in football.

How should one imagine your working hours?

Currently, I am working quite intensively to finish grants. I wake up at around 7am and go to bed at midnight, which amounts to approximately thirteen hours of work after subtracting non-work activities. However, I do not mind the long hours as I enjoy my work. In my free time, I make sure to engage in sports, go to the gym, or pursue other interests.

What do you enjoy most about going to the gym?

My favourite exercise is the deadlift, as it helps me to maintain good physical and mental health by increasing blood flow. However, what I am most excited about is the reading material I bring with me. Currently, I am reading Bata's (Czech enterpreneur in shoe industry) biography, which, despite being about a different industry, is inspiring. I enjoy learning how to apply useful concepts from other fields to science.

Do you recall who had the greatest impact on your decision to pursue physics?

Even as a child, I was fascinated by a wide range of subjects. Fortunately, my parents indirectly fostered my curiosity and gave me complete freedom to explore my interests. I believe that if you want to pursue something seriously, such as business, it is best to gain practical experience. However, in physics, it is much more complex; you cannot simply borrow a laser. That's why I participated in mathematics and physics competitions and Olympiads during high school, until I discovered the Young Physicists Tournament. I have fond memories of this competition because it closely resembles real science compared to regular competitions. Instead of just receiving an assignment and working on it individually, teamwork is required to solve problems that may not have a clear solution.

In this context, I would like to highlight Petr Pavlíček, the former director of the Mendel Grammar School in Opava. He introduced a colleague to the gymnasium who encouraged us to participate in the tournament. I joined for the first time in my third year, and we advanced to the world round held in Korea. Although it was maybe not a significant event 15 years ago, we had to seek funds to attend the competition, and fortunately, Czech company Kofola supported us at the last minute.

What were your impressions of the tournament?

I remember a lot of excitement and I think we were very competitive back then. We also met a lot of friends from different countries, for example, I remember a football match with the Brazilian team. The competition itself was very interesting because the problems are openly formulated.

Each team works on the solution for five to six months and usually has a completely different approach. The competition made me understand how important it is not only to have good science content, but also to be able to communicate it and raise funding. I still have many friends from the tournament days that I see on a regular basis, and I often meet scientists at international congresses who also participated in the competition in high school.

From our interview, it is evident that Šmejkal is enthusiastic about contributing to the further development of research. Despite advice from his friends and colleagues to take a break, Šmejkal remains committed to his work. He draws inspiration from many areas and finishes our interview with saying: "Do you know what Beatles did after they finished, they successful album? They started to work on the next one.“

Libor Šmejkal is a research team leader in the INSPIRE group at the Institute of Physics, Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, and a researcher at the Institute of Physics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. He studied theoretical and experimental physics in Brno and Vienna and received his PhD from the Academy of Sciences and the Charles University in Prague.

Šmejkal is currently researching topological and magnetic quantum matter, developing theoretical physics tools for studying functional quantum matter on supercomputers, discovering unconventional magnetic crystals, and developing materials and conceptual devices that can contribute to sustainable nanoelectronics of the future.

He was awarded the Falling Walls Science Breakthroughs of the Year 2023 award for his theoretical work in alter-magnetism and non-dissipative nanoelectronics. In 2021, the Euro-European Association for Magnetism awarded him the Young Scientist Award, and the Czech Head of Science awarded him the Doctorandus Award for Natural Sciences. In 2020, he earned one of the Best Dissertation Werner von Siemens Prizes.