Ing. Alice Hospodková, Ph.D., head of the Department of Semiconductors and MOVPE Laboratory, is convinced that in physics it is as hard for women as it is for men. The only exception is the time of motherhood.

You are one of the few female heads of departments at FZU. How do you see the issue of equal opportunities in the physics community?

The term "equal opportunity" is a somewhat nebulous term, although it is fashionable to use this phrase. For scientists in the natural sciences used to working with exact quantities, it is probably a difficult concept to grasp. It cannot be easily captured by statistics on the staffing of various jobs. It is certainly not possible in physics, which far fewer women than men are fascinated by.

If the question is aimed at whether in science it is harder for women than for men, then my personal answer would be no, but except for one period, and that is the time of motherhood with young children. This is a period of hard trade-offs in terms of how much time I can devote to the children, work, partner and sleep.

There is no easy solution, everyone is looking for their own compromise. Moreover, the ideal time for parenthood usually overlaps with the time when a young scientist is expected to go abroad for two years for a postdoctoral fellowship. It is usually complicated even for dads, but it is much more complicated for moms.

You are actively involved in the popularization of physics. What could motivate high school students to take an interest in this "unpopular" subject?

At high schools, the greatest motivation clearly comes from good teachers who can pass their enthusiasm for the subject to the students entrusted to them. I'm sure we all remember this well from our student days. Being an educator is simply a huge daily responsibility that perhaps not all teachers are aware of in the rush of all their duties and worries.

I strongly believe that the first step in getting students to like subjects like maths, physics or chemistry has been taken: giving teachers a pay rise. It may seem mundane, but salaries are everything. It is the first prerequisite for increasing an interest in teaching among good students so that schools that prepare future teachers can choose. "Equal opportunities" for men and women are also important. This reduces the likelihood of the education system employing people who simply do not belong there and do more harm than good.

But even after the salary increase, it's a bit depressing when we calculate how many years we will have to wait before the change actually takes effect: it takes a few years to increase interest in teacher education, it takes five years for future teachers to study at university, it takes a while for new teachers to improve their teaching, it takes at least four more years for these new teachers to educate their students, and it takes at least five more years of study and three more years of experience before society feels the impact. So, the estimation is that we have to wait at least twenty years.

Fortunately, even among current teachers there are many excellent ones who were not discouraged by their former salaries. We must hold them in high esteem. It would be nice to find or offer some voluntary platform (something like a dating site) for establishing personal partnerships between scientists and teachers who would be interested in such collaboration. I believe that many scientists would enjoy such collaboration and would be happy to make time for it. I would sign up for it right away.

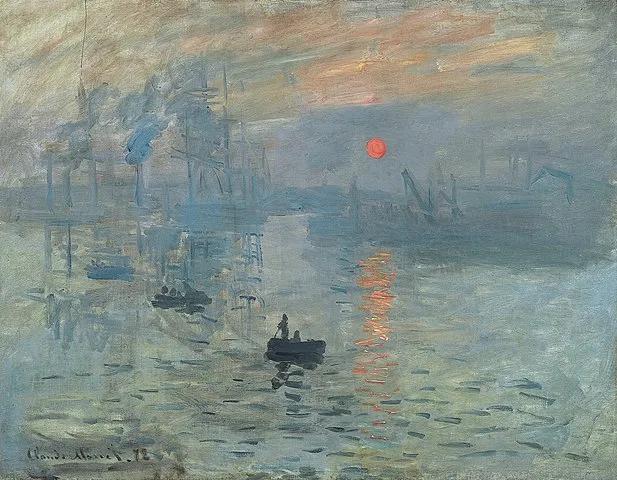

What is your favourite physics-themed artwork?

Not a trite question. You probably had a book or a film in mind, but the first thing that I thought of was Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise. The painting beautifully shows that the longer wavelength light scatters less and only red and orange light passes directly through the foggy atmosphere of the harbour, while the short wavelengths are scattered in the thick layer of atmosphere and in the fog that the light passes through.